Afghanistan 360

January 19, 2022

Afghanistan, a country in Central Asia, is known for its family-centred culture along with its hospitality and loyalty. Afghanistan is in a region of the world known for its high conflict. Bordered by Iran and Pakistan, it is home to several extremist groups like the Taliban, ISIS, and al-Qaeda. The country has been at war in modern times since 1979 when Soviet Russia invaded the country and occupied it for a decade. There has been no strong economy, institutions, industry, or progress. The society in Afghanistan is fundamentalist and tribal. There has never been a strong central government, so there has been no social contract between citizens and their government. Afghanistan has typically had tribal governments where citizen allegiance lies.

The US went to Afghanistan in 2001 to eliminate al-Qaeda, a global terror organization headquartered in Afghanistan under the protection of the Taliban, the fundamentalist Islamist organization that controlled the country and its government. Afghanistan is very poor so the citizens do not have TV or radios or access to the internet or international newspapers. They do not have access to information about global events or even about anything happening in their own country. Citizens thought that US troops were Russians because that is all they knew. They also didn’t know who al-Qaeda or the Taliban were. They did not know about the attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001, the biggest act of terror of the century. America has been in Afghanistan for 20 years, the longest sustained military conflict in US history. In that twenty-year period, the US military was able to subdue the Taliban, who previously took control of the country and created a haven for anti-Western terrorism to flourish. Earlier this year, however, the US ended its occupation and the Taliban quickly retook control.

controlled the country and its government. Afghanistan is very poor so the citizens do not have TV or radios or access to the internet or international newspapers. They do not have access to information about global events or even about anything happening in their own country. Citizens thought that US troops were Russians because that is all they knew. They also didn’t know who al-Qaeda or the Taliban were. They did not know about the attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001, the biggest act of terror of the century. America has been in Afghanistan for 20 years, the longest sustained military conflict in US history. In that twenty-year period, the US military was able to subdue the Taliban, who previously took control of the country and created a haven for anti-Western terrorism to flourish. Earlier this year, however, the US ended its occupation and the Taliban quickly retook control.

The Taliban are an extremist Islamic group that came to power in Afghanistan in 1996 and imposed and brutally enforced Sharia Law based on fundamentalist Islamic dogma, which was most oppressive on women and girls. Girls were terrified into stopping going to school. They were to cover themselves in a burqa, a piece of clothing that covers the entire body, when in public. Women were unable to work in anything except healthcare because only women could treat women. It was a requirement that every woman had to be accompanied by a man. If a woman broke any rules, they were punished severely. They have also banned many forms of the arts. With the recent takeover, many of the same laws were reinstated.

During the occupation by the US military, there was an attempt to shape the country like the United States. Democracy did not sit well with the locals, in large part to the cultural and tribal differences between Western culture and Afghan culture. The US wanted to get its military, police, and government stable and uncorrupted. Corruption has been widespread throughout Afghanistan. The people are terrified to fight back against corruption. A lot of people were terrified about the very sudden withdrawal. The US did not know enough about the culture in Afghanistan and the citizens did not want to westernise. Many Afghans were resistant to changes brought about by the military. Many Afghans, particularly women and girls, benefited from US intervention and influence. Regardless of the benefits to so many, the cultural change did not take hold. Why is that? The ethnic and cultural divide was more meaningful than the US had ever anticipated. Corruption in the government, military, businesses and other institutions is accepted. Drugs have also been a huge issue in the country, the majority of the world’s opium and heroin comes from Afghanistan. Drugs bring in a lot of money, about $1.8 to $2.7 billion, according to a report in November of 2021 by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. In addition, neighbouring countries like Pakistan have been trying to undermine the stability of Afghanistan.

The Taliban have been condemned by many countries for their brutal reign and laws. They have committed genocide on hundreds of civilians, denied food and other supplies from the UN, and adopted a scorched earth policy, burning everything to the ground in their wake. In 2021 after a 20-year presence, the United States withdrew its troops from Afghanistan as part of an agreement with the Afghan government. The Taliban were able to easily and quickly take over without resistance. During evacuation efforts, a bomb attack in the Kabul airport on August 26th killed 182 people seeking to flee the country.

I interviewed U.S Army Colonel Paul Larson, a Senior Leader for the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon and served three tours in Afghanistan. He worked on the U.S military pullout earlier in 2021. Colonel Larson told me why the decision was made to leave Afghanistan now, “There’s a lot of people that thought that it didn’t matter anymore. We went there in 2001 to prevent more terrorist organisations from committing attacks. Terrorist organizations couldn’t use Afghanistan as a home base. Realists in the US government think Pakistan and India are the primary relations and have nuclear weapons and the US needs to focus on the relationship between those two countries.”

Question: What were your experiences in Afghanistan?

Answer: “In 2005 to 2006 as a Captain, I commanded a company of 200 paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne Division in southern Afghanistan. During that time I ran an austere Forward Operating Base (FOB) in a very remote region in the Zabul province along the Pakistan border. Our operations were tactical, that is, “local.” We were focused on the local populace, community

institutions, and practical/sustainable infrastructure. We fought the Taliban village-to-village, valley-to-valley–always in an effort to protect the Afghans. This was before the days of any semblance of the Afghan Army, so I allied with groups of local militias who fought for their tribes and villages. Alongside these kinetic operations (think firefights here) we also endeavoured to assist with community governance to strengthen institutions and finance micro development projects to expand the local economy. These development projects were mostly agrarian-based: drip irrigation, high-yield wheat seed, etc. Additionally, I focused on important social initiatives to assist women and girls that included a project to provide looms and non-electric powered sewing machines to women as they could earn their own money as well as schools that allowed girls. I worked with USAID and several NGOs to do this, but I was honoured to be recognized by President Clinton at a Clinton Global Initiative summit in NYC in 2009. And, Seal was at my table which was pretty cool too.

In 2010 as a Major, I taught an elective titled, “Winning The Peace” while I was an assistant professor at the United States Military Academy at West Point. I focused on the nexus between the theory, literature, and scholarship of development, social sciences, and counterinsurgency (COIN) doctrine with my experience as a practitioner. We studied revolutions and revolutionaries, insurgencies and counterinsurgencies, and I sprinkled a little Peloponnesian War in there because we Army guys look for any opportunity to mention Thucydides…. 🙂

I went back to AFG from 2014-2015 as Lieutenant Colonel, but this time I commanded a battalion of 1200 paratroopers. Our operations on this tour were “operational” which means country-wide. We conducted operations from the Hindu Kush mountains in the north along the Chinese border to deserts of the south along the Iranian border. This tour did not include any development–it was all fighting all the time, and I don’t really like talking about it, but many of the soldiers under my command received medals for valour in combat. Nonetheless, I did gain a better appreciation for country-wide issues such as the Pashtun/Hazara divide, the influence of the Pakistani Taliban, the malign effect of the opium/poppy trade, and the ineffectiveness of the Afghan Security Forces (ASF).

I went back for another year in 2016 as a Colonel. This was my first truly strategic tour. I served as the lead strategist for the theatre commander, GEN Nicholson. My focus during this tour was (primarily) external actors. I wasn’t a commander here, but an advisor. Nonetheless, I worked to shape outcomes on issues such as the U.S/Pakistan relationship (or, more pointedly, the lack thereof,) gaining and maintaining support and funding from NATO, and improving our relationship with the Iranians (esp. with regard to the Chabahar port along the Gulf of Oman–a strategically located deep-water port that the Chinese have their fingers in…) I also worked to influence domestic politics by fighting my colleagues on the National Security Council, working with the Senate Armed Service Committee, briefing CODELs, and accompanying my boss to brief the President and staff at the White House. It was very educational and illuminating to view and work on these issues in a global context and I learned a lot about foreign policy and in particular, how policy is made (punchline: it’s messy).

My last year in AFG was 2018-2019. I was in command of a Brigade Combat Team of about 5000 soldiers from the 10th Mountain Division. This tour was interesting because I led operations in southern AFG and (although I didn’t think I’d enjoy this) I was the commander of the Kandahar Airfield (KAF). As it turns out, KAF was, at that time, one of the ten busiest airports in the world and I loved the job. The bad news was that I saw the writing on the wall–the government was corrupt beyond measure, the Afghan Army was a complete mess, and the mood of the Afghan people has already shifted to supporting the Taliban. I knew, as soon as I set foot on the ground in Kandahar that the environment was different. My friend, General Abdul Razeq (who, despite evidence of corruption, was viewed as a George Washington-type figure by the Pashtuns) was killed by his bodyguard in the palace gardens when we were walking together towards a helicopter. As I reflected on my own mortality that day, I knew in my heart that the war was over. The Americans had failed, the Afghan “National Unity Government” had failed, and the Afghan people were, again, going to suffer even more hardship.

The best thing in Afghanistan was the food. The people there are some of the nicest people you will ever meet.”

Q: What was the hardest part of your job during the withdrawal?

A: “Leaving behind our Afghan friends that have worked with the coalition and sacrificed so much because they believed in the western vision of what Afghanistan could be and the potentiality of them getting hunted down by the Taliban. When I got to Afghanistan in 2005, we had to find translators to help communicate, which were kids. My first interpreter was 17 and wanted to be called HBK (short for heartbreak kid) and he learned to speak English by watching action movies and wrestling. Kids were using bootleg VHS tapes and learning English. These created the sense of what life could be like and they wanted that. I have become emotionally attached to the people and families and it was hard to watch their lives get destroyed and it was sad to watch. It was hard to abandon so many people. It was hard to watch any progress go backwards.”

Q: What is your opinion on the military pullout?

A: “Part of the tenentants we have were the civilian control of the military. The military withdrawal was when we tried to follow orders unemotionally. We could provide military advice to elected officials. Many in the military thought it was a mistake and we could still make slow progress. The Trump administration said we were pulling out and we said ok. Once the decision was made, we did it. Officially, We followed orders based on the US constitution and as morally as possible. Unofficially, I will say that the pullout was a really big mistake. Demonstrated to our allies that the US military is not a good ally.”

Q: What did some of the US do in Afghanistan to help civilians?

A: “The biggest we thought we had the most positive impact was started schools and universities in Afghanistan. There were very few schools, with one textbook, the Quran. It was illegal to teach girls something other than the Quran. Education was the most important thing we focused on. We worked with UNICEF and the UN to normalise education. We tried to integrate the internet to get citizens a free flow of information. We tried to normalise different gender roles and put women in positions of authority and power and get an education. Healthcare was vastly improved. There was a poor diet and air quality. Many wouldn’t survive past their forties.”

Q: What do you expect in the future in Afghanistan?

A: “I think that the Taliban is having a lot of difficulties running the country. It’s different between running the country and insurgency. Governing is hard. The Taliban are failing. Afghanistan does not generate electricity and buys it from neighbouring countries. The entire country was run on generators which caused pollution. I hope they asked for assistance from the international community. I hope the international community has conditions to ensure the Taliban follows human rights and morality. It’s hard for me to be optimistic about the country’s future. I’m optimistic that the US affected so many people in a positive way that the seeds of progress in Afghanistan will grow in the next generation. We have to wait for the kids to grow up.”

Q: Many students are thinking about joining the military or are preparing for careers that will require them to interact with other cultures. What advice would you give them?

A: “I would say it’s not going to be easy but it will be rewarding from the perspective of someone who enlisted right out of high school. You are expected to be an adult overnight. It’s easy for some and hard for others. Once you join the military, you are expected to be a full-grown person and be responsible for everything. You are going to be assigned to different places and an entirely new culture. It’s rewarding because you learn more about yourself. I found it challenging at first because of the change. Do research before joining because you can tailor your experience to what you know you can do and your interests.”

I interviewed another Afghan veteran, Steve Russ. He was in a special forces unit in 2019, spending six months overseas. He currently works on responding to terrorist incidents.

Q: What were your experiences in Afghanistan?

A: “I honestly loved my deployment. I am obviously fortunate to say I saw combat and came home with no injuries. If I did not have a family I would have done multiple tours. I loved our mission and loved helping the good people of Afghanistan. Most of them truly appreciated our presence there. Overall my experiences were very good, all things considered.”

Q: What is your opinion on the military pullout?

A: “This war had to end but I do not agree with the manner in which we ended. We were there far too long and the Afghans never really took charge. Towards the end, they should have been leading all operations and taking over security of their country but they never really stepped into that role.”

Q: Could the government have done anything differently during and after?

A: “Hard to say from a strategic level but I believe we should have started the handoff a long time ago and slowly reduced operations led by the US. In the end, we should have evacuated our civilian partners, US civilians and then the military should have been the very last phase in my opinion. I believe we could have avoided the disaster that happened at the Kabul airport.”

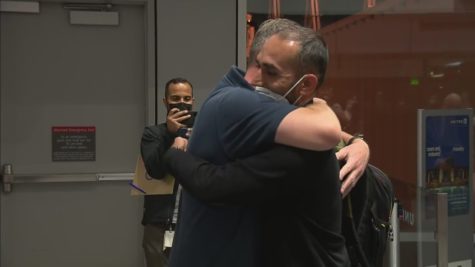

There are several Afghan families living in Broomfield. Recently, a translator, Ahmad Siddiqi, and his family moved to Broomfield. He was close friends with U.S troops, specifically two locals named Scott and Heidi Henkel. Henkel and his friends realised they needed to get Siddiqi out. With a

a lot of pressure and with not a lot of help from the government, they managed to get him and his family out. Heidi runs the Broomfield Afghan Evacuee Task Force, which helps refugees settle into Broomfield. She informed me that the task force has successfully moved four families and are currently helping them settle in. One more family will be coming in during the month of January.

Scott Henkel is a retired Army captain. Ahmed Siddiqi was his translator. Ahmed and Scott became close friends over hundreds of missions. They had not seen each other in 15 years. Siddiqi and his family were living in Kabul when the Taliban swept through the country. The trip between the airport and their home quickly became dangerous, until they got help. After weeks of hard work and help from the Henkel’s, Siddiqi and his family got to Broomfield. There has been, and continues to be, a huge outpouring of support for the family. They have recently moved into their own house in Broomfield.

There are a lot of people still in danger. Many people who were close to U.S troops are in danger of being killed or thrown in jail. Many Afghans in the U.S still have family in Afghanistan, which they are understandably still worried about. A lot of people who have escaped often do not want to talk about their experiences.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afghanistan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taliban

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2021_Kabul_airport_attack

https://coloradosun.com/2021/10/11/colorado-family-afghanistan-nabiyars/

https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/Afghanistan/Afghanistan_brief_Nov_2021.pdf